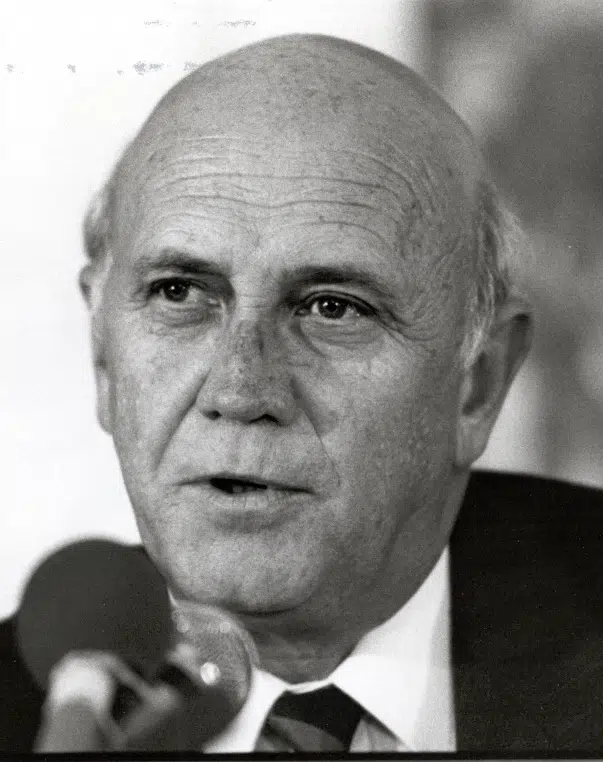

Almost nothing suggested that former South African president Frederik Willem de Klerk would be the one to dismantle apartheid.

He was born into a family of politicians of the nascent apartheid state, became a member of Parliament in 1972, and was complicit in—even supportive of—all the evil committed under apartheid during numerous ministerial posts. But while serving as president, de Klerk stunned the world in February 1990 when he removed the ban on opposition political movements, including the African National Congress, and released political prisoners, including the individual with whom he would later share the Nobel Peace Prize—Nelson Mandela.

De Klerk’s death at the age of 85 this week has been widely reported in the New York Times, the BBC, der Spiegel, the Daily Maverick, and other international media. Yet none mention that, under his leadership in 1991, South Africa joined the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and fully dismantled the country’s nuclear weapons arsenal.

De Klerk believed that nuclear weapons, having lost their deterrence value following the end of the regional conflicts, would subsequently burden his government. Two weeks after assuming the presidency, he held a top-secret meeting of advisors in which he requested a plan to rid the country of nuclear weapons. Those who attended agreed, though some rather grudgingly, as he recounted in my 2017 interview with him.

A president in favor of nuclear disarmament. Though de Klerk apologized for his complicity and support for the evil committed under apartheid in his last public message, he will never be acquitted. He benefitted from the racially discriminating structures, while serving as an instrument that perpetuated the system—at least until he negotiated the Afrikaners out of power. But when he had the chance to terminate the nuclear program, he did so with expediency and conviction.

Was de Klerk’s anti-nuclear stance born from strategic foresight, distaste for the nuclear warheads, or opportunistic awareness of the necessity? The world may never know. Still, unlike his predecessor, PW Botha, he had the courage to act on a nuclear disarmament opportunity when he saw it.

The Cold War was winding down by the time de Klerk took over the presidency. He made sense of international political events like the fall of the Berlin Wall and Soviet Perestroika in terms of realpolitik—politics based on practical rather than ideological considerations. In the nuclear realm, he displayed an inner certainty that moved him to act. He sought to reduce South Africa’s isolation that resulted from its Cold War nuclear ambiguity. If Pretoria—the city where the country’s executive branch sits—dissolved its nuclear arsenal, South Africa would regain respect in the global community of states.

An international and domestic balancing act. When de Klerk ordered the disarmament in early 1990, the South African government was not yet on a clear path towards democratic majority rule. On the international stage, UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and US President George H.W. Bush courted de Klerk. Meanwhile, the Conservative Party—a looming right-wing threat emanating from paramilitary groups and white extremists—exerted pressure at home. Opposition to the government’s reform plans risked a coup.

The newly elected de Klerk wanted a quick return to normal political relations with other states. While the world would be reassured if Pretoria renounced nuclear weapons, saying as much would have had disastrous domestic political repercussions. Still, soon after taking office, de Klerk issued secret orders to dismantle South Africa’s six nuclear warheads and a seventh then under construction. He waited to announce the historic decision until March 1993.

Almost three decades later, in my 2017 interview with him, de Klerk revealed that his distaste for nuclear weapons preceded his presidency. He had decided that if ever he became president, he would review South Africa’s nuclear weapons program. He had that chance by 1990—and seized the denuclearization opportunity.

De Klerk’s nuclear rollback was complete and verifiable. Not only was South Africa free of nuclear weapons, but the development served as a catalyst for Africa as a nuclear-weapon-free zone. In 1995, President Nelson Mandela and other African heads of state signed the Treaty of Pelindaba, which forbade atomic bomb testing and banned nuclear weapons from the African continent.

South Africa remains the only country to have gone full circle on nuclear weapons. The South African National Party politicians initiated a nuclear weapons program during the 1970s and de Klerk ended it in 1989. De Klerk expressed the hope that South Africa’s example might inspire the nine leaders of other nuclear weapons states—the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea—to eliminate their arsenals. The world can only hope that, over time, they do.

|