For an easily excited and easily excitable people, once described as the happiest people on the face of the earth, Nigerians – well, some Nigerians – have become the constant butt of jokes for and by politicians.

Indeed, the Nigerian politician appears to have the number of Nigerians and is just some dials or clicks away from sending the Nigerian on a fool’s errand.

And nothing best captures this absurdity than the outcomes of elections since the beginning of the Fourth Republic in 1999. For 16 years, the Peoples Democratic Party, PDP, ruled Nigeria. Caused to be convinced that the PDP failed them, the All Progressives Congress, APC, packaged a vigorous campaign in 2014/2015 election season and succeeded in ousting the former. The APC’s headship of Nigeria is in its eighth year and the jury is already in, with a cacophonous Babel.

In both spheres, Nigerians were promised better life – in fact, abundant better life – through the instrumentality of political party manifestoes. Mind you, every four years since May 29, 1999, we’ve had elections and, at each turn, there were campaigns laced with an effusion of promises, some realistic, others utopian at best, with a tincture of ridiculousness.

But between 2003 and 2015, the choices before Nigerians had been limited, in a manner of speaking, because they were almost always pitched in making a choice between two major political blocks – PDP and any other potent opposition party. Not that there were no other parties, it just so happened that the suggestion that Nigeria would always be consigned to the realm of two dominant political parties as espoused by the Ibrahim Babangida regime, which decreed the Social Democratic Party, SDP, and the National Republican Convention, NRC, into existence, appeared to be very true and real. Since 2015, Nigerians had been stuck with the PDP and APC.

But individuals have been known to drive movements and act as change agents. Enter Peter Obi and the Labour Party, LP. And Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso of the New Nigeria Peoples Party, NNPP. Frustrated out of the PDP, Obi chose to run on the platform of LP, while Kwankwaso re-energised the NNPP.

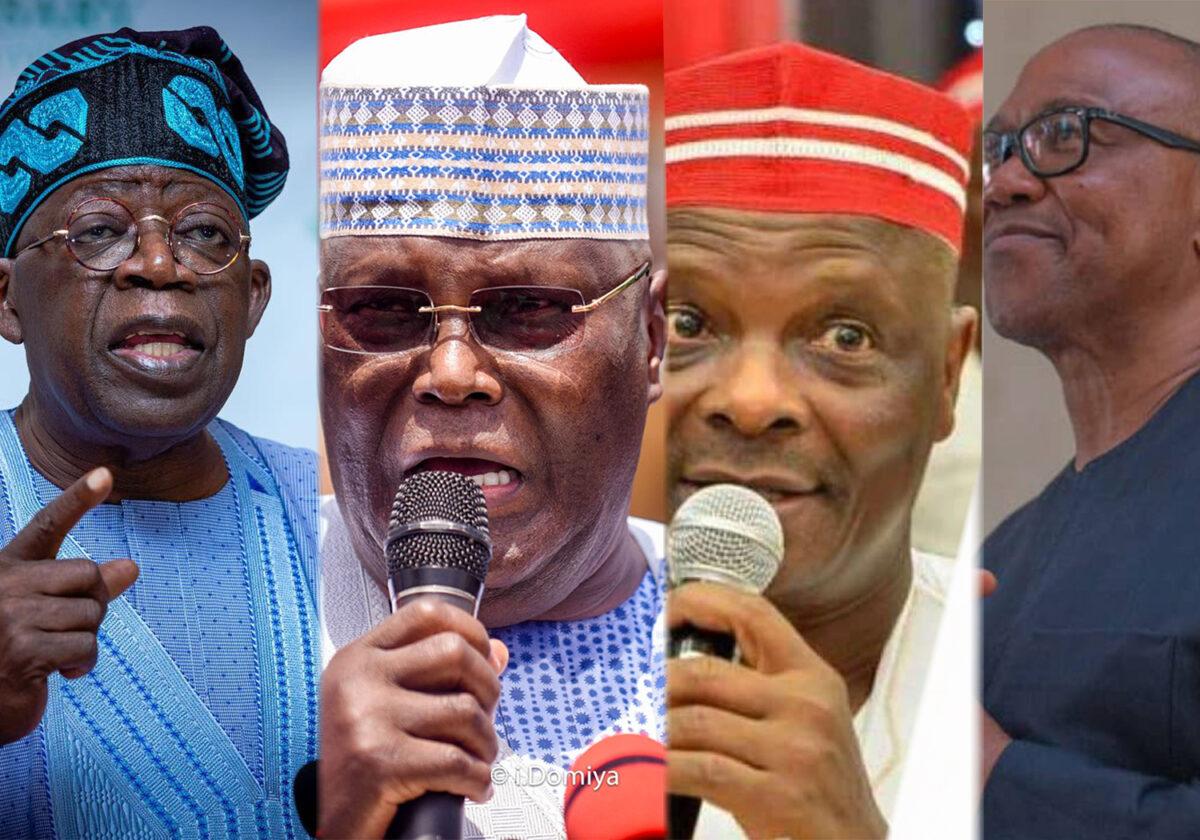

So, the 2023 general elections, specifically the presidential poll, are now a four-way race. Obi and Kwankwaso are joining Atiku Abubakar of the PDP and Bola Ahmed Tinubu of the APC in the presidential race.

So, how do these individuals and their political parties hope to go about mobilising Nigerians and laying out their plans of action? With or without prejudice to the jaundiced mode of virulent, abusive, unintelligent, silly and sometimes shameful acts that have dogged the campaigns of the PDP and APC, while not leaving out the followers of Obi, better known as Obidients, and to a very less extent, Kwankwaso of NNPP, the two leading parties have left much to be desired in the way candidates and surrogates have redefined the art of abusive campaigns.

Worse still, the rallies and campaigns have been short of concrete plans of action to redeem Nigeria but long on provocative and sometimes shameful slogans.

Therefore, the question becomes pertinent: What are these politicians campaigning on? What is the content of their campaign manifestos? Beyond sloganeering with fanciful phrases and cliches headlining their manifestos (Renewed Hope: Action Plan For A Better Nigeria, Covenant With Nigerians, Rescue Mission, It’s Possible: Moving Nigeria From Consumption To Production, Pledge To Create A New And Better Nigeria), what concrete policy initiatives are they presenting to Nigerians and how do they hope to activate and actualise them? They may not. Where people are not held to account for their actions, anything goes. Those before them did not, were never held to account, hence the shambolic polity that Nigeria has become.

In this comprehensive treatise, Vanguard will be looking at the manifestos of these four candidates and what they are promising Nigerians vis-a-vis contemporary yearnings and demands of the people. This report will examine the policy direction of the candidates as put down in their manifestos along the lines of the freshness of ideas, presentation style, depth of policy options, lucidity, factuality, practicability and other such indices that would make for an intelligent, yet a simple breakdown of same, with a view to building a better nation.

Employing a thematic analytical format, different spheres of Nigerian life in key sectors will be outlined for ease of comparison. The sectors will include but would not be limited to the following:

Agriculture

•Power

•Unemployment

•Restructuring

•Economy

•Health

•Education

•Corruption

•National Security

•Oil and Gas

•Debt Overhang

•Foreign Policy

Some of the manifestos come across as mere utopian documents, seemingly packaged to satisfy the urge for psychological masturbation of a relief, just as the practicability or effectuation of some of the initiatives appear unrealistic and dubious. Again, for an easily excited and easily excited populace, in a polity of clashing socio-political, ethno-religious and damaged economic environment, when you present a pulverised populace with sand, they are likely to mistake it for food.

Starting today with a general overview, the next three days , will see the candidates’ different policy initiatives as contained in their manifestos, pitched against each other. The Weekend title will take a broad look at the economy – revenue generation, oil and gas, power, unemployment, agriculture and others. The Sunday title will look at the issue of national security. And on Monday, governance issues like rule of law, restructuring for better governance outcomes and others.

But these manifestos, how did they come about? Are they products of group thinking or just the idea of a candidate? Is it inclusive (participatory)? Or, is it exclusive (leadership-directed)? Inclusive processes of manifesto writing, according to Hazan and Rahat, “allow broad participation of the rank-and-file during the drafting process and formal decision-making by intra-party referendum or party congresses”. They explain: “We reason that more inclusive manifesto writing leads to manifestos of greater internal acceptance, and hence relevance to the candidates.” Conversely, the leadership-directed style delivers the mindset, thoughts and vision of the candidate with minimal input from experts in different spheres.

History of manifesto

In the Encyclopaedia (Britain), a manifesto is described as “a document publicly declaring the position or program of its issuer”. It adds: “A manifesto advances a set of ideas, opinions, or views, but it can also lay out a plan of action. Manifestos are generally written in the name of a group sharing a common perspective, ideology, or purpose rather than in the name of a single individual. Manifestos often mark the adoption of a new vision, approach, program, or genre.

They criticize a present state of affairs but also announce its passing, proclaiming the advent of a new movement or even of a new era. In this sense, manifestos combine a sometimes violent societal critique with an inaugural and inspirational declaration of change. Although manifestos can claim to speak for the majority, they are often authored by a nonconformist minority and are linked to the idea of an avant-garde that signals or even leads the way to the future”.

Among many notable literary and artistic manifestos are Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s “Futurist Manifesto” (1909); “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste” (1912) by David Davidovich Burlyuk and others; and André Breton’s “Manifesto of Surrealism” (1924). Several manifestos have played an important role in the history of social movements and political ideas.

But one of the most famous political manifestos is Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s The Communist Manifesto (1848).

It became one of the principal programmatic statements of the European socialist and communist parties in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The “Communist Manifesto embodies the authors’ materialistic conception of history (“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”), and it surveys that history from the age of feudalism down to 19th-century capitalism, which was destined, they declared, to be overthrown and replaced by a workers’ society. The communists, the vanguard of the working class, constituted the section of society that would accomplish the “abolition of private property” and “raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class.”

The Communist Manifesto opens with the tantalising words: “A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of communism” and ends by stating, “The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Workingmen of all countries, unite”.

Today, the only unity among workingmen of all countries is the continued agitation for a better life. But as for the proletariat, they are yet to attain the level of the ruling class.

This then leads to another question for Nigeria’s leading presidential candidates: How well do their manifestos relate to the challenges of Nigerians?

They all give hope: Hope is better served for breakfast

Francis Bacon said, “hope is a good breakfast, but it is a bad supper” (Works of Francis Bacon, Vol 7 (1859) ‘Apophthegms contained in Resuscitatio’ no 36.

Now, put in context, the manifestos of the four leading candidates, in all fairness and on the surface, promise hope. But since the devil is always in the details, it is for Nigerians to examine, with a fine tooth comb, the content, context and objectives of the manifestos.

Atiku’s presentation espouses Where We Are, What To Do, The Principles and How To Get It Done. Hinging his manifesto on his five-point agenda – on education, restructuring, economic prosperity, security and unity, Atiku makes useful references to successes of the PDP administration between 1999 and 2007. It is presented in three broad parts covering the economy, human capital development and governance

Kwankwaso does something similar in another way. He talks about his Pledge to Nigerians, an uncommon commitment to deliver and makes projections. He is of the belief that frugality will lead to the economic recovery while not discounting the place of security and unity. He takes on 27 issues which cover everything under the sun

For Peter Obi, it is about context and what We Will Do. His is bold and sometimes revolutionary. Just as he has been speaking in public about the need to pull people out of poverty, his manifesto makes some suggestions that are new but may have to contend with systemic challenges. Obi focuses on seven areas with sub-themes.

In Tinubu’s manifesto, he talks about Goals and Solutions, focusing on 17 areas of interest; but re-affirms that he would build on the current successes of the Buhari administration. He takes on all issues and offers what he considers the best solutions.

As we dig deeper in the following days, readers will discover the singular thread that runs through all the manifestos: A promise of a better Nigeria.

Curiously, they are all friends and the only streak of divergence can be located in the seeming marginal difference in approach.

As for what they promise, it is almost the same thing – unity, enhancement of national security, economic recovery and the enthronement of a polity of possible equals.

TOMORROW: Their Economic Blueprint and why Nigerians must be weary of sweet talk. For instance, the candidates are promising to increase the generation and distribution of electricity, a sine quanon for economic recovery and stability to between 15,000 and 30,000 megawatts within 24 months. How practicable is this? Each of them discusses how to deal with the debt overhang as well as harness the potential in the oil and gas sector to earn revenue. Will their strategies work? The different spheres that constitute the economic landscape like agriculture, MSMEs, employment and the like, and what are their policy direction?

|